Our Verdict

Keys from the Golden Vault has some gaps in its heist plan, and it suffers under a system not designed for such capers. However, its settings and stories often shine, even if some need a bit of polish to become gems worth stealing.

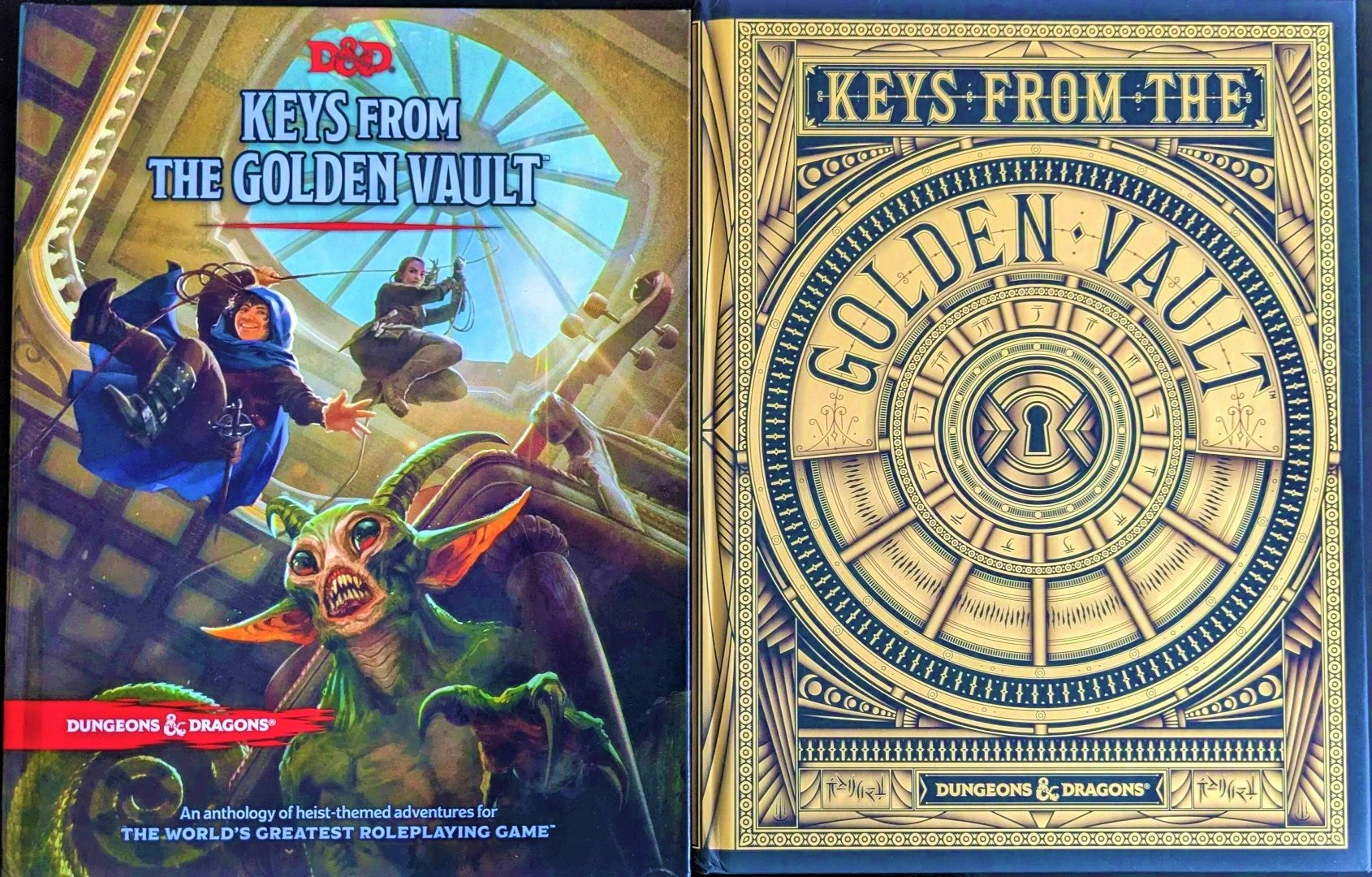

On the surface, Keys from the Golden Vault is a treasure trove of adventures. The latest D&D anthology offers a range of high-stakes heists, sneaking you into devilish casinos and magical maximum security prisons. Each one-shot sets a memorable scene, polishing beloved crime caper tropes and adding new, creative spins. But not all that glitters is gold. Some aspects of the book feel shallow, and its potential is limited by the 5e system itself.

After a full readthrough, and guiding two parties through the book’s level-two adventure, I’m ready to spill the beans on the Golden Vault. Grab your thieves’ tools, because we’re about to crack this book wide open.

What is Keys From the Golden Vault?

Keys from the Golden Vault is an anthology of adventures, structured similarly to Candlekeep Mysteries and Journeys Through the Radiant Citadel. Each chapter is a standalone DnD one-shot, but there’s also a loose overarching theme to link them if you fancy.

For this book, that theme is heists. The Golden Vault is a mysterious organisation that employs operatives to investigate, infiltrate, and steal on their behalf – typically in the name of a just cause. The book’s adventures each represent a different heist, taking players from levels one to (Ocean’s) 11.

What’s in Keys from the Golden Vault?

The adventures on offer are pretty varied. Some are going for a sandbox feel, where there’s no clear solution to the scenario and player creativity takes the lead. Some are focused on social interactions, allowing you to totally bypass combat if you play your cards right. Others feel more like traditional dungeons – which makes them feel less like actual heists, but are worth having for those who relish the more standard ‘combat and exploration’ experience.

Keys from the Golden Vault also has a wealth of memorable detail. Nearly every adventure has some creative flourish that sticks with you. Expect cowboy casinos, possessed prison wardens, talking paintings, and zombie musicians. The real star in this department is Affair on the Concordant Express, the ninth-level adventure by Justice Ramin Arman. It’s the most funny, unique, and replayable adventure in the book, and one of the most enjoyable reads I’ve had for some time.

What isn’t in Keys from the Golden Vault?

Despite these successes, I found the book lacking in many other places. The first of these is the Golden Vault itself. The lore explaining the organisation is thin and not particularly exciting. The book may not be designed as an overarching campaign, but Journeys Through the Radiant Citadel shared the same structure, and that book was filled with worldbuilding and setting gazetteers. Despite the Golden Vault’s huge potential, the book gives you very little to work with.

Some of the adventures feel similarly shallow. The Stygian Gambit is my example here, as I ran this adventure for multiple groups. It sets a very compelling scene, but it’s then entirely down to the Dungeon Master to make the adventure work. There’s no linear plot or clear-cut solution for the heist, and, while the adventure offers plenty of tips for the DM on how the party might go about things, it offers very little support communicating that information to players.

When run as-written, my players struggled with analysis paralysis and frustration. After I drafted entire new scenes, added a new cast of NPCs, and created a small calendar of events to drop more obvious clues, the party made much more progress.

The players had plenty of positive things to say about The Stygian Gambit, but everyone involved agreed: this is an adventure that requires confident players and a very involved DM to function. Despite being filled with pre-written adventures, it seems Keys from the Golden Vault still expects you to do a fair bit of your own writing.

The bigger problem with the plan

I think this lack of support is part of a larger problem: D&D isn’t equipped to run a heist. Planning is a central part of the heist genre, and the 5e system has no real mechanics to support this.

D&D games are highly reactive; typically, you rock up to the dungeon and respond to whatever DnD monsters the DM has thrown your way. Keys from the Golden Vault requires players to spend a lot of time talking through plans, with no action involved – which can be unclear, unstructured, and even boring for players.

Many heists also rely on timing, but D&D leaves time entirely up to DM guesstimation. It’s all well and good telling us we only have 48 hours to complete the job, but with no way to track this, it becomes an obsolete piece of information, used to artificially put pressure on players while not actually meaning anything.

Some of the adventures do attempt to add features for managing common heist tropes. You’ll see the odd table tracking the suspicion levels of guards, but these aren’t universally applied.

Keys from the Golden Vault offers creative and colourful adventures, but even its best attempts fall short without mechanics designed to accommodate a heist structure. And, in the aftermath of the DnD OGL scandal, with D&D players more open to trying new systems than ever, it feels important to mention the alternative heist games available. Systems like Fiasco and Blades in the Dark – whatever their own shortcomings – have been handling heists far better, and for far longer.