Writing news for Wargamer on the regular means that I come across a lot of up-and-coming board games. These new tabletop games come in all shapes and sizes, from strategy games with armies of meeples to compact card games with a handful of components. From the board games we’ve covered in this month alone, I’ve spotted a few that are following an interesting trend worth at least a brief chat about – and that’s a changing treatment of colonialism.

A surprising number of board games are set in – and often mechanically based on – historical periods of widespread oppression. While this may be considered a leftover relic from a board game era gone by, where the European creators were moving away from war themes, this board game history isn’t so ancient – the ‘classic’ colonising game Puerto Rico only came out in 2002, after all.

Attitudes seem to be changing to board games set in colonial periods, however – for every case like Puerto Rico or Archipelago, there seems to be another like Scramble for Africa, where insensitive treatment of these themes courts criticism, and is stopped before it can start.

I’ve collected three new board game announcements from February that show just some of the ways that historical board games are beginning to respond differently to colonialism – and, more widely, socially significant events in global history.

Libertalia: Winds of Galecrest

At the start of February, American tabletop publisher Stonemaier Games announced it’s making a revised edition of Libertalia, a pirate-themed card game that takes its name from a legendary 17th century Madagascan pirate colony. Libertalia: Winds of Galecrest has been given a full makeover by Bahamian artist Lamaro Smith, whose illustrations have transported Libertalia from the Golden Age of Piracy to a more fantastical setting, complete with flying ships and anthropomorphic animal sailors.

Smith’s transformation of Libertalia is a stunning one – judging from the photos released on Libertalia: Winds of Galecrest’s Facebook page, the new edition is sleek, colourful, and refreshing. It activates the magpie part of my brain that wants to buy board games just to look at them. Libertalia’s new look isn’t the only thing that’s received praise online, however. “It’s cool to have an artist from the Caribbean illustrating a pirate themed game”, says BoardGameGeek user Asa Swain in one forum. User Monstars23 agreed that the decision was an “amazing touch that adds game appeal”.

Whether Smith’s heritage had any influence over the decision to use his designs can only be known to the Stonemaier team, but the publisher did speak out on changing attitudes to race in Libertalia in other ways. In a Facebook livestream promoting the game at the start of February, developer Jamey Stegmaier explained the decision to remove a “freed slave” character from the game – one that Stegmaier says Stonemaier considers an “unfortunate and controversial” feature of the original. “We don’t want slavery in this game in any way”, he says. By adding a fantasy factor and removing this character, Stonemaier made the call to erase colonialism from Libertalia’s surface almost entirely.

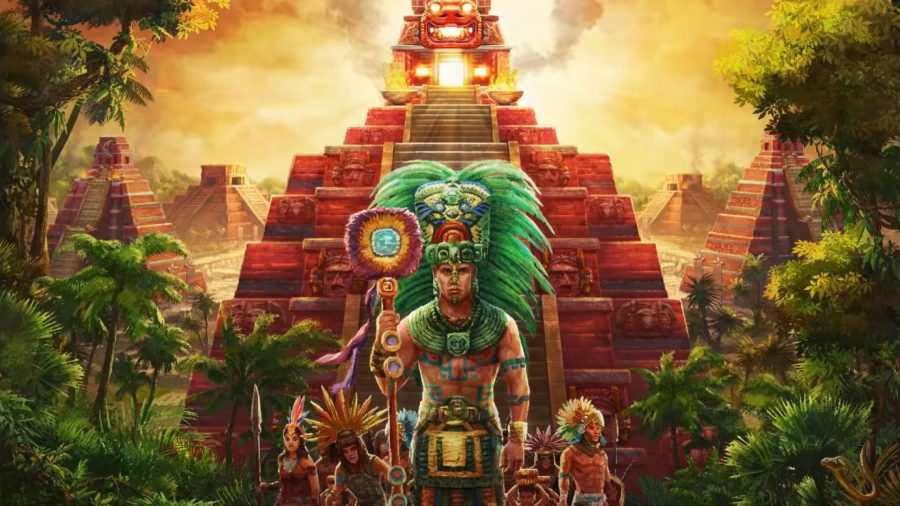

Ahau: Rulers of Yucatán

Ahau: Rulers of Yucatán is a strategy board game set in the Classic Period of the Maya (250-900 AD) of South America, which arrived as a Kickstarter project at the end of February. While Mayan civilisation has already set the scene for previous board games (Maya or Tzolk’in, anyone?), Ahau stands out by selling itself as a game that is as historically accurate as possible.

According to the game’s Kickstarter page, Hungarian publisher Apeiron Games claims to have gone all in on its true depiction of the Maya period – Mayan cities are shown in their “exact geographical location” on the board; the game’s illustrations are sold as being “historically accurate”; and the designers worked with historical consultants from the U.S., to Mexico, to Guatemala. One of these experts praised the game for its depiction of history, saying “Maya culture is not simply an aesthetic backdrop, but rather an integral part of the game”.

War gamer: check out our guide to the best WW2 games

Apeiron could have made the choice to focus on the Spanish conquest of Maya, which took place in the 16th century, rather than Maya’s Classic period. However, the period chosen seems to keep the focus exclusively on Mayan society rather than merely its interaction with invaders. Taking Ahau in isolation, Maya is not reduced to its relationship with its eventual colonisers.

Apeiron demonstrates a tremendous amount of respect for the ancient culture of the countries it profits from in developing the game. The different nationalities of the team behind Ahau are displayed on the Kickstarter page, which seems to say that Apeiron takes pride in the diversity and accuracy of its product.

Tindaya

Tindaya, a mountain once considered sacred by the islanders of Fuerteventura, is now getting its own board game set during the colonial invasion of the 15th-century Canary Islands. Recently launched on Gamefound, this is the debut game of Spanish publisher Red Mojo Games, and it’s designed by the company’s founder Lolo González – who also happens to be from the Canary Islands himself. Like Ahau, Tindaya was created thanks to a whole lot of research – González didn’t let being born on the Canary Islands stop him travelling home to visit museums and discuss the archipelago’s traditions in order to make his game as accurate as possible. In a recent interview with Wargamer, González explained that the game’s mechanics are all designed to replicate real historical events and beliefs present in the game’s setting.

This goal meant Red Mojo ended up with a game that goes some way towards challenging colonialist and environmentally exploitative norms that often end up in the eurogame genre. Players are actively punished by the game for using up too many of the islands’ resources or for failing to provide their tribe with food and shelter. Resource-hungry eurogamers who are used to using meeples as just another resource to be spent may find their usual techniques flipped on their head. And when meeples in historical eurogames often represent indigenous people (just look at the brown discs that represented ‘colonists’ in the first edition of Puerto Rico), having to care for and consider your tribe more carefully sends quite a different message.

In a game like Tindaya, it’s not just a question of being historically accurate, but of where you place your historical focus – for González, as he says, “the game was always about the tribes”. Tindaya was presented for evaluation at the 2022 Zenobia Awards – an award that celebrates historical board games made by marginalised creators, which in itself is further evidence of changing attitudes towards global and colonial narratives in historical games.

It’s still worth viewing colonial-themed games with a healthy amount of scepticism when they’re announced, of course; the question ‘why make a game about this’ always deserves an answer. But these games do inspire a fair bit of optimism in me – we’re seeing increasingly diverse teams create thoughtful and creative games which will hopefully still be fun to play, despite focusing on indigenous cultures rather than so-called ‘civilising’ Europeans, with non-white people in uncomfortable supporting roles.

Tindaya and Ahau have both already achieved their crowdfunding goals, and Libertalia’s new edition is receiving praise and anticipation online, which seems to point to people other than me being equally enthusiastic about the games themselves – and perhaps the changing trends they represent.