In November 2021, when the Black Lives Matter movement was particularly visible in global news, Games Workshop released a blog post stating that Warhammer 40k is a satire. According to GW, while the Imperium of Man is “the cruellest and most bloody regime imaginable” (to quote the foreword to Rogue Trader), it is presented with “humour, irony, or exaggeration” to reveal its vices and flaws to “scorn, derision, and ridicule”.

This statement from GW is political. It says “we believe in and support a community united by shared values of mutual kindness and respect”… “we will never accept nor condone any form of prejudice, hatred, or abuse in our company, or in the Warhammer hobby”. Wargamer absolutely agrees with that sentiment. But claiming that the Imperium of Man is presented satirically simply fails to acknowledge the reality of modern Warhammer 40k – and from that disconnect, discord grows.

Warhammer 40k started out as satire

The first edition of Warhammer 40k, Rogue Trader, was written in 1987 largely by Rick Priestley, an up and coming young game designer who had cut his teeth co-writing the original Warhammer Fantasy battles. It was a hodgepodge of ideas from many sources: Frank Herbert’s Dune, 2000AD comic strips like Judge Dredd and Nemesis the Warlock, Michael Moorcock’s fantasy and sci-fi, Philip José Farmer’s The World of Tiers, Bryan Ansell’s Laserburn wargame.

We can add to that Priestley’s lived experience in mid 20th century Britain; the long-tail of the Second World War and the end of British Empire; the ongoing civil discontent of the ‘70s and ‘80s between trade unions and the government; the UK’s ongoing military operations in Northern Ireland; state sanctioned support for the South African Apartheid government; and the Falklands war. All fed into an early 40k corpus that was politically charged and anti-authoritarian.

Warhammer 40k has never had satirical focus

The Rogue Trader era of 40k was certainly political, but it wasn’t focused. There are throwaway gags referencing pop culture, like Inquisitor Obiwan Sherlock Clousseau, and niche references to British culture – like a dig at the cultureless planet Birmingham, which was named after a rather unfairly maligned UK town.

Even so, the game’s general message was typical of most punk pop culture of the period: authorities are oppressive, corrupt, and bureaucratic; advanced warfare is still barbaric; systems of oppression inevitably create the rebellions that they use to justify themselves; and so on.

Since Rogue Trader was published, Warhammer 40k has been developed and expanded with a ridiculous quantity of content. It isn’t one single thing any more – it’s a complex of Warhammer 40k books, Warhammer 40k Codexes, miniatures, Warhammer plus animations, tie-in Warhammer 40k games on PC and console, even marketing materials. There’s more of it than any one person can engage with, and the focus has been split even further.

To call it all “satire” undersells how diverse, tangled, and contradictory it is. If your first encounter with Warhammer 40k is seeing a cardboard marketing standee of a Primaris Space Marine, it’s not going to be a satirical experience. The plot of the Dawn of War games, as told in those gloriously hammy cutscenes, is a heroic pulp adventure. The Arminka Lesk novels – though they demonstrate just how bloody, cruel, and wasteful Astra Militarum warfare is – nevertheless depict Arminka as a valorous and dutiful heroine who embodies universal military virtues of pride, comradeship, and self-sacrifice.

For satire to effectively criticise something, it needs to be focused. The target must be clear, and relentless energy must be applied to undermining it. Satire doesn’t have to be funny, but comedy does make a great vehicle for it because it prioritises immediacy, impact, clarity, and formulating a message that can reliably make it through to an audience of possibly disinterested consumers. Anyone claiming this is all true of Warhammer 40k today faces a serious uphill struggle.

Warhammer 40k gives the horrors of the Imperium dignity and style

Warhammer 40k has always been cool. It’s a game, and a setting with blank space to which players will add their own narratives. It’s full of ideas and characters that when considered on their own terms, as something to play with in a universe without consequences, are simply awesome; even if they are objectively appalling, when we apply contextual knowledge from the outside world.

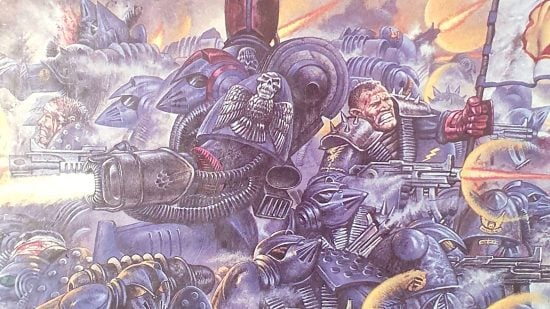

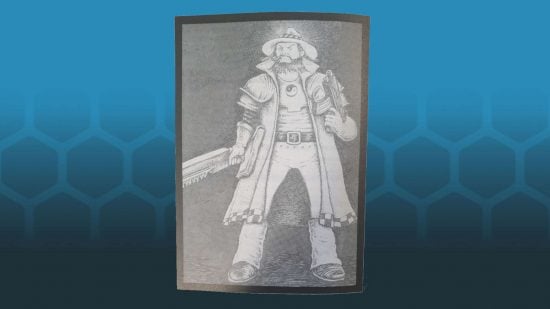

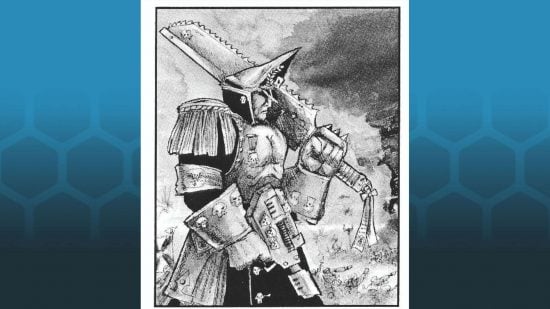

The very first artwork of Space Marines shows them to be snarling, scarcely human, bionically enhanced brutes. But they’ve always looked dope. John Blanche’s illustrations of Imperial Guard Commissars were directly inspired by the barbaric real world military practice of executing soldiers for failure to follow orders – but he still gave them the sickest drip you’ve ever seen.

Making something look cool is not a good way to suggest it sucks. In fact, if there’s even a hint of coolness about something, it’s very hard to make a criticism hit home. Video essayist and author Lindsey Ellis provides an extensive analysis of this phenomenon in the video embedded below. In it, she compares the representation of the Nazis – generally agreed upon as The Absolute Worst People – in Mel Brooks’ comedy The Producers against serious social drama American History X.

The Producers presents Nazism and neo-Nazism without dignity or depth, while American History X is a dramatic exploration of the horrors of American white supremacy, with that story’s worst villains portrayed as stoic characters with strong jawlines and transgressive tattoos. American History X may have been created with acute critical intent, and The Producers as a farcical musical joke – but, of the two works, American History X has more neo-fascist fans.

Warhammer 40k’s other fictional content overwhelms its satire

Warhammer 40k lore has developed in directions that directly undermine its ability to criticize the real-world inspirations of the Imperium. While Rogue Trader presented an Imperium that’s arguably as atrocious as the forces that opposed it, the threats it faces have since escalated wildly, weakening the setting’s satirical base by giving the Imperium more convincing excuses to be awful.

The Drukhari aren’t just Eldar raiders, they’re Hell-Raiser style torture vampires. The Tyranids aren’t just goofy-looking bugs, they’re a galaxy spanning extinction event. Chaos Space Marines aren’t just rebels, they’re malevolent, murderous cultists in league with metaphysical powers that want to torture every human soul for eternity. In that ignoble company, the Imperium of Man is clearly the lesser evil.

The irony and exaggeration remain, but they’re now the background to a battle for survival, told from the point of view of (usually) relatable, sympathetic and enjoyable Imperial characters – satirical motifs no longer pointed at a satirical target.

While the Imperium is clearly corrupt, inefficient, and ruinous to its citizens, the reality of its situation has changed a critique into a question. Are these acceptable prices for continued survival? Are these inevitable consequences of continued survival? Great fodder for sci-fi debates, but ineffective satire.

Saying Warhammer 40k is simply satire fails to engage with it

To make it clear – anyone who thinks the politics of the Imperium of Man are a model to work from is wrong. But the primary reason for their wrongness isn’t because 40k is a satirical critique of their ideology; it’s because Warhammer 40k is fiction. Using Warhammer 40k to support real world beliefs is like painting a door onto a brick wall and then trying to open it because you saw it in a cartoon.

By the same token, insisting Warhammer 40k is just a satire (and the common corollary that people who can’t see that satire are delusional) doesn’t help the discussion – because it doesn’t engage with the many different things you will find within 40k’s warped and inconsistent tapestry.

Every text is multi-layered, seeking to entertain and bring the author’s personal perspectives to life, but also carrying a certain baggage of genre expectation – including pulp adventure, procedural war dramas, horror, mystery, comedy, and much more. Which of the many possible readings we take away depends on what we bring to the work as readers, and there isn’t a correct hierarchy of interpretations.

Wargamer still welcomes GW’s statement that “real-world hate groups – and adherents of historical ideologies better left in the past” who “seek to claim intellectual properties for their own enjoyment, and to co-opt them for their own agendas” aren’t welcome in the hobby. They bring the mood down, to put things mildly.

But simplifying the complex media beast down to a single genre it only vestigially resembles doesn’t help us to accurately understand it, or to unpick and address the different motivations that bring people to the hobby. If we want to create and sustain a positive and inclusive culture in the hobby, we need to start with a frank assessment of what’s actually being offered up by Warhammer 40k as it is today – however uncomfortable to our sensibilities the answers may be.