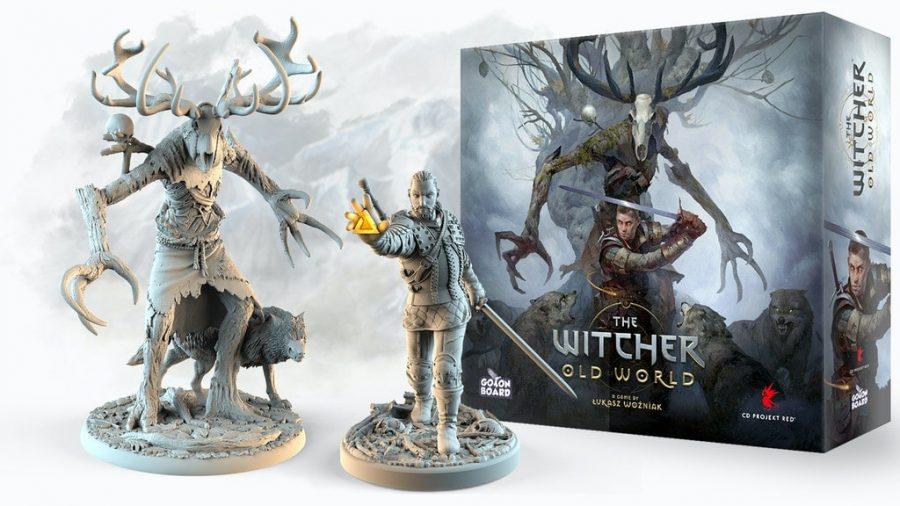

A series of novels, a trilogy of videogames, and a Netflix television show: The Witcher might be the most recognisable fantasy franchise of the moment. And as with most popular franchises, the board game industry wants in. Revealed back in February to much fanfare, and launching its Kickstarter campaign in May to even more success, The Witcher: Old World is the latest attempt to bring the Continent and its ashen-haired monster hunters to the tabletop.

It’s fair to say the board game has generated some excitement. Its crowdfunding campaign was fully funded within 19 minutes, with over 45,000 backers pledging more than $8,000,000, and has opened again today for late pledges. A collaborative effort between The Witcher videogame publisher CD Projekt Red and tabletop studio Go on Board, the board game’s promise of recreating the adventuring choices and frenetic combat of the videogames has, unsurprisingly, proved an alluring package for many.

For designer Łukasz Woźniak, however, that package took some time to gestate. Having previously run a board game review channel on YouTube, Woźniak’s chance to collaborate with CD Projekt Red on a monster-hunting board game stemmed from the release of The Witcher’s earlier tabletop adaptations: 2014’s The Witcher Adventure Game, and 2015’s minigame-turned-digital-card-game Gwent.

“I got in touch with them years ago about the possibility of reviewing their games,” Woźniak tells Wargamer. “And because I was designing games for many years, one of my first questions was ‘By the way, is the door open to create another Witcher board game?’ They said they weren’t closed to that possibility, but the game idea would have to be interesting enough for them to get involved.

“Every year or so I would ask them if the door was open, and I waited for my mind to come up with an idea worthy of The Witcher franchise; when I felt I had something that would fit into that world.”

A game of two halves

The idea that finally crystallised in Woźniak’s mind is what he broadly labels an “action-adventure game”. It’s a vague genre term loved by the videogame industry for its wide applicability, but in the case of Old World carries a distinctly more purposeful usage. The game is split neatly into two halves: one spanning the action; the other the adventure, which Woźniak is keen to prove collectively captures the primary elements of the franchise, especially The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt.

He explains that those players “looking for the things that witchers do, which is to hunt down monsters and kill them”, will find plenty of that in Old World. Combat is driven by deck-building card play, which has you chain together combinations of attacks to multiply your damage-dealing in one vs. one Witcher-monster combat. You’ll gain more fighting moves, additional magical signs, and new mutagens, letting you slay the toughest monsters and accrue point-scoring ‘trophies’ before you opponent players.

But before the fight comes the hunt, and the narrative elements that players might recognise from the videogames. Travelling from place to place across a central map, you’ll stumble upon encounters, and be forced into dilemmas, whether that’s helping those in distress, taking time to rest, or providing a passerby with herbs and medicine.

“The action part represents the core of The Witcher universe, which is being a witcher, fighting, and using those milliseconds to inflict as much damage to your opponent as possible,” Woźniak says. “And the adventure part draws from a wide variety of stories, themes, and characters that you may encounter.”

But despite these clear halves of gameplay, the combat was front and centre in Woźniak’s design process. The central map and character development came quickly after, but his initial vision was to create a board game that represents the combat of The Witcher, and not only that of the videogames.

“I came up with the idea when I was listening to an audiobook of one of The Witcher novels,” he says. “When I was listening to that, I realised that the mechanics of the game have to underline the complexity of the combat system that you read about, or experience in The Witcher videogames.”

Tabletop trophies: These are the best board games in 2021

The idea is that Old World’s deck-focused combat can go some way to replicating the finesse of Geralt’s fighting. Making an attack, adding a parry, quickly slashing the enemy, and throwing out a magical sign, before finishing the combat with a powerful blow: it’s intended to evoke the acrobatic, if relentless, close-combat duelling that fans will be familiar with.

“The board game isn’t capable of doing what the videogame or the TV show does, which is to show how the Butcher of Blaviken can murder some people,” he says. “But that’s why, first of all, you take your decisions in the adventure part of the game, and, secondly, when you use the cards and combine them as a player, we did our best to help you imagine that not only mechanically, but thematically.”

As with other tabletop games, entrenching Old World’s theme in the player’s mind to drive home the weight of their actions was partly achieved through creating a captivating visual presentation of the game, and a slick player interface that immerses them in the fictional world. But Woźniak places more emphasis on how the game metaphorically paints the picture of your fight, and riffs on the ‘theatre of the mind’ that’s so essential to tabletop RPGs.

“You may begin your combo by playing a card called Shockwave, and follow it up by a Crippling Strike, and then follow this card by a Cover, and finish it with a Staggering Blow,” he says. “As you see those cards combined in your head, it’s first of all really fun to connect the cards that you have, and to make the most out of the deck that you have created.

“But thematically, it’s quite easy to imagine that the monster was coming at me, so I first threw a magical sign burning it up a little bit, which opened me up to perform a fast attack and add more damage. Then I took a cover, preparing for its attack or dodging it, or maybe reinforcing my defence, and finishing it with a strong blow with my sword.

“There are also people who would describe what they do while they play their cards and – I am talking about myself here – would stand up and present to everybody at the table what they’re doing, or how they are imagining it in their head.”

Thematic inspiration

Old World wears its inspiration on its sleeve, and not only through its branding. Anyone who’s had a cursory playthrough of The Witcher 3 will recognise familiar elements in the board game: cities, potions, signs, mutagens, witcher schools, and more have been lifted from the blockbuster RPG.

For Woźniak, the videogames offer the most expansive representation of The Witcher universe, organising its various elements into the best vessel through which to explore Andrzej Sapkowski’s fantasy world. But, he says, constructing Old World wasn’t a matter of slavish imitation. To do that would be to sacrifice its potential.

Games for two: Our pick of the best couples’ board games

“The videogame genre is something that works within different confines or different boundaries than the board game genre,” he says. “So while creating the board game, my idea was to represent The Witcher universe as well as possible and create an exciting, fun player experience.

“A board game that has physical components and rules that you have to understand before you play is something different than the videogame where you get into it right away, and the details of the game mechanics as you go along. There are things that are similar, but obviously recreating a videogame in a board game format would be detrimental.”

This attempt to partially divorce the board game from its primary source material also explains its setting. Set years before Geralt of Rivia, in a time when monsters are more common, witchers roam in higher numbers, and the schools that train them have not yet been reduced to rubble, Woźniak had room to manoeuvre. He could include new locations, build original characters, and impose events without fear of stepping on existing lore.

The Old World setting also served a functional purpose. A prevalence of witchers drifting the land meant each player could control their own monster hunter, with no Geralt-type stealing the limelight. “We wanted to create this adventure game, and we wanted to make it competitive,” Woźniak says. “So when you play with your friends, it’s not that you are playing only alongside one another or co-operatively, but you’re competing against one another. When one of the other witchers is fighting a monster, you’re rooting for the monster to defeat them.

“There are five Witcher schools and all of them are competing to become the most renowned among the others. When you meet them in a tavern, it would be very plausible that you would tell them what you think about their school, and they will propose ‘OK, so let’s brawl to see who’s stronger.’

“It allows for more interaction. Even though it’s a big adventure game, you are involved when you take your turn, and you are involved in different ways when other players are doing their things.”

This new setting for the franchise is intended to preserve the fundamental features of The Witcher universe. Monster-hunting is still the game’s hallmark, players learn new witcher skills as they progress, and the world is brought to life through similar methods of character interaction.

Game plan: Our pick of the best strategy board games

“There were a lot of elements that got into the game very early on, and we never even thought about removing them because they felt so intertwined”, Woźniak says.

“There are many aspects of the game that I believe have to be there regardless. Potions, bombs, trailing the monsters, monsters being different in strength and in special abilities, fast and strong attacks, all five witcher signs: those are all given, and were there from the very beginning.”

But when integrating such obvious brand touchstones in a new title, it’s a fine line to walk between authentic recreation and cheap tie-in. As a designer, Woźniak felt he had to take both a broad and narrow perspective to his adaptation. The broad concerns the general feel of the game; ensuring its story and universe are similar to that experienced elsewhere in The Witcher franchise and align with the core aspects of the videogames.

The narrow, meanwhile, concerns artwork, names, and smaller elements that might directly riff on previous titles, and which must be carefully balanced in their tabletop form. Woźniak gives the example of monster trailing. Implemented in The Witcher 3 through a pseudo ‘detective vision’ mode that highlights the footprints of your prey, Old World hands you cards that explain the monster’s weakness in flavour text, and grants you a combat buff to use in the final fight.

“You do this by playtesting the game with different people and talking with them,” Woźniak says about this process. “Observing their emotions and decisions, talking to them after the game, and honestly feeling them out whether they really felt like they were playing the Witcher or just another adventure game.

“It’s helpful to playtest on a very early, very unattractive prototype because then it’s not the artwork or even the specific names, but the whole general feel of the game that’s tested.”

Fan Responsibility

Feedback is a common theme in his account of the game. In the three months between announcing the game in February and launching its crowdfunding campaign in May, thousands raised their opinions, comments and hopes about the game. Many were eager to see their beloved monster included, their favourite character nodded to, or their cherished questline recreated.

“It’s easy to lose your vision for the core of the game,” Woźniak says “And so it’s always important to filter the ideas people send and have the vision and the main player experience always be your guideline.

“But at the same time, it’s very beneficial. Even before we launched the campaign, we have changed some things visually, added some things, or started working on some things that we hadn’t even thought of before people had suggested them.”

The potential for The Witcher: Old World is clear. A combat-focused, tabletop recreation of the latest fantasy world to have swept popular culture, which is keen to capture the core tenets of its alluring world, while making room for original storytelling to suit the medium; it could be brilliant.

“It can sometimes be disingenuous, but in our case, nobody expected we were going to get such support. We are very happy, very grateful, and we feel the weight of the fanbase of The Witcher universe. And that’s why we’re doing our best to pour everything that we can into this game.”

The Witcher: Old World’s crowdfunding campaign is open for late pledges now.