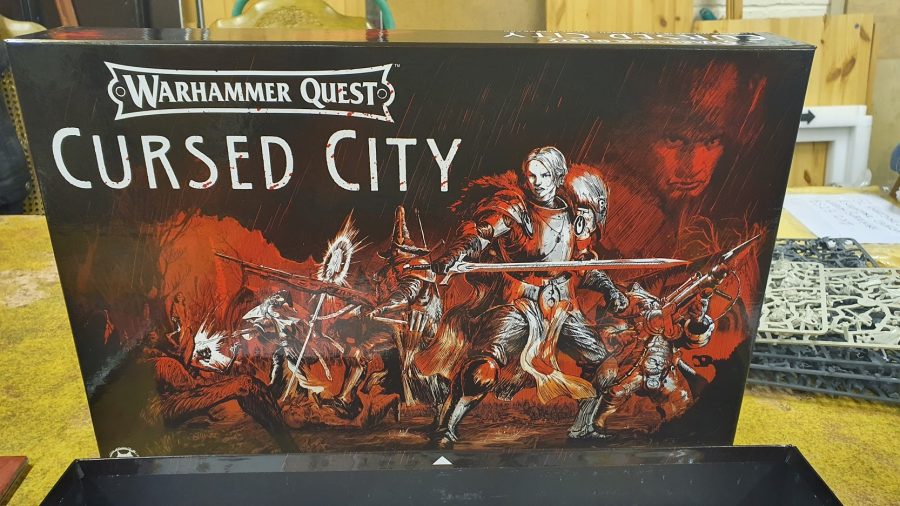

Let’s run a little experiment. How many of you who clicked on this article can remember a little game called Warhammer Quest: Cursed City? It’s a trick question, of course; we all remember it. For those of us who exist in the persistent fugue state of delirious excitement and cynical impatience that is the Warhammer fandom, Cursed City is a name that lives in infamy, longing, or perhaps both, long after its many weeks as the talk of the (tiny plastic) town.

In case there are any of you living outside the bubble: Cursed City is a $199 / £125 boxed fantasy miniatures game that Games Workshop hyped up in its videos, streams, and blog posts at the beginning of this year – insinuating it would be an episodic game with expansions, like its bestselling predecessor, Blackstone Fortress.

GW released the game in April, very quickly ran out of online stock worldwide, and then, just five days after release – as legions of fans waited with bated breath for news of restocks – it suddenly, retroactively announced the game was no more. Did it stage a gracious, openhanded climbdown that invited fans to commiserate with it over the unintended loss of a cool game it had really wanted to make? Did it heck.

Instead, GW sent a single, bizarrely offhand tweet which declared, with the flint-eyed confidence of a giant face on a 1984 telescreen telling you that Oceania has always been at war with Eastasia, that Cursed City had always been a limited run.

Cursed City is sold-out on https://t.co/Xd5jLuY4wp and we are not expecting it to return online.

Many copies have been sent to local stores across the world. Please check with your local Warhammer store or independent retailer to see if they can help.— WarhammerCommunity (@WarComTeam) April 15, 2021

Inevitable fan outrage ensued, and the saga became the latest in a long line of tail-chasing internet controversies over Games Workshop products that, for one reason or another, not everybody was able to get a copy of. Nowhere, dear reader, is the phrase ‘artificial scarcity’ used more liberally in anger, or with less economic expertise, than in Warhammer comment threads.

The story’s final act came on May 16, when GW slipped into its latest hype-building pre-orders article a new, separate boxed set containing the enemy character miniatures from Cursed City – but curiously bereft of even the slightest mention of their ill-fated origins. The game, it seemed, was being – ahem – airbrushed out of history.

But we’re not here to talk about what ‘went wrong’ with Cursed City. The likely whys and wherefores were patiently explained by industry commentators almost immediately, and it doesn’t take a genius. Cursed City used components from around the world; at some late stage, some parts presumably became unavailable, and by then it was simply too late to stop the train.

Bummer for GW, bummer for fans – but it is just the way it goes sometimes (especially when covid’s sent half the planet’s logistics up the swanny), and Warhammer’s generous crop of conspiracy theorists has, to date, not come up with a more convincing explanation for a global, multi-billion-dollar company deliberately not selling them big boxes of toys at a characteristically fat profit margin.

No, what’s more interesting about this episode is what it says about how GW chooses to communicate with the outside world.

Talking to people

At any stage during this series of events, GW could have actively ‘got ahead’ of the story. It could have used its excellent, carefully cultivated editorial-slash-marketing mouthpiece, Warhammer Community (and a little help from humble independent outlets like Wargamer) to explain to fans what went wrong, authentically share in their disappointment, and collectively build excitement for the next Big Thing (which, as it happened, would have been Age of Sigmar third edition).

That would have drawn a proper line under the story, and netted the firm a heavy dollop of goodwill, to be squirreled away, and cashed in the next time a major project went tits-up.

Imperial glory: Our guide to Warhammer 40K’s Imperium factions

Instead, it simply pretended everything had gone to plan, in spite of the copious, freely available evidence to the contrary.

GW’s masters should have known that nobody would believe it had only ever meant to produce enough Cursed City boxes to serve a fraction of the demand it had drummed up. They should have known press reviews would confirm the unmistakable references to planned upcoming expansions printed in the game’s materials – and they stuck with that line anyway.

That’s breathtakingly weird, when you think about it. GW doesn’t ‘owe’ anyone a game to buy, regardless of how much it advertised one. It’s perfectly free to cancel any product, any time, and give literally any reason it likes, or none. Even axing the game with no explanation at all would likely have been less inflammatory than the message they chose. To anyone unaccustomed to GW’s modus operandi – and even most of us who are – it was a deeply confusing move.

Growing pains?

At this point, I should acknowledge that very few people – and certainly not me – are in a position to give Games Workshop business advice, given it’s nearly doubled its profits in the last year, and more than doubled its share price in the past five years, while other toymakers and retailers have crashed.

The totality of what GW’s doing right now is making it more cash than ever before (which is good news for the company’s fans, as much as for its gleeful investors – more money for them means more new toys for us).

Prepare for launch: Read our review of Age of Sigmar Dominion

But, to my mind, all that success, and the constant consolidation of its market-leading position in a growth industry, is itself an argument that a serious change of communications strategy is in order.

GW still has a powerful monopoly over its fan army – but that army is growing so large now that it can no longer disavow itself of its every misstep with magical thinking, trusting that everybody will forget everything the moment their next shiny plastic-wrapped box hits the shelves. And, perhaps more importantly, I just don’t think it needs to act that way any more.

A cult no more

In its long history of shepherding a slowly growing customer base of gainfully employed, 25-50-year-old men (and their adolescent sons) from one high-margin purchase to the next, GW’s customer relations have always appeared to benefit from a benign form of the same information-controlling mechanisms used in brainwashing cults.

Knowledge of what’s coming next in Warhammer’s various product lines is jealously guarded, and deployed sparingly; details and release timelines are kept vaguer, for longer, than in other parts of the games industry; product information is released piecemeal, in the form of salacious hints and teasers, or ‘accidental’ early leaks of new rules slipped into product packaging. Even its new preview streams are mostly careful to steer clear of offering any solid timescales for the products they reveal.

How much of that is a deliberate strategy by GW to forcibly stretch a marketing calendar (which wants to be predictable) around volatile, unpredictable manufacturing schedules, and how much is simply a disconnect between the firm’s internal and public-facing organs, is impossible for us outsiders to know.

The result is the same, though: a fan-base on tenterhooks, hanging on the company’s every word, perpetually engaged in furious detective work, just to puzzle out what they’ll want to buy that year, and when it’s coming out.

It’s brilliant for engagement, of course – but add in the hard realities of manufacturing and retailing tabletop games worldwide – especially during a pandemic – and you’ve got a powder keg of customer rage ready to blow, the moment you do promise something, and, for whatever reason, it doesn’t come off as planned.

Holding the line: Read our new Cadian Shock Troops review

One can understand why GW might historically have chosen to batten down the hatches over episodes like this – even if its chosen PR line makes little sense. Talking frankly about the business realities might, at one time, have risked losing a touch of its Wonka’s-factory mystique, perhaps even endangering its unique industry position.

But, GW, it’s not the 1980s any more. You made it. You’re turning over £350 million a year. The 90s kids are hitting their well-paid 30s, and your savvy combination of marketing and owned digital media is starting to make your games seem mainstream enough that those thirty-somethings will keep buying your toys for years to come – and maybe drag their friends in, too.

You have to accept it: you’re not a cult any more, you’re a massive mainstream games company. That comes with (even more) piles of money, but it also comes with so much scrutiny that, when something important goes loudly wrong, simply telling your customers ‘that was our plan all along’ is going to cause more problems than it solves.

Sons of the Lion: Read our guide to Dark Angels Space Marines

The good news, though, is that it also means you’re big enough to explain, maybe even apologise, when something bad happens, without the whole house collapsing about your ears. Calming down a bit, and opening up to your hyperactive community about mistakes and challenges, will not bring GW tumbling down. You’re not that vulnerable any more.

So, just start talking to the outside world like a normal company. It’ll save you, and us, a lot of headaches in the happy wargaming years to come.